In this article I will detail several concepts and techniques for creating great puzzles. These concepts can be used to improve your existing puzzles or to help complete or refine your puzzle designs.

Sequence Puzzles

Most puzzles require the player to do actions in a certain sequence to solve them. The simplest form of this is a key and lock – find the green key to get past the green door.

You can use more complex sequences to add complexity and difficulty to a puzzle, but you must be careful not to create puzzles that are just complex without being interesting, challenging, or fun.

To make better sequence puzzles, you can use non-linear sequences. A non-linear sequence is one that might require the player to undo or re-do some parts of the sequence, or to skip an aspect of the puzzle and come back to it later. When you do this, it is an opportunity to obscure the solution without being unfair, and it is also an opportunity to show players different facets of the mechanics.

Constraints Make a Puzzle

Puzzles are often created from constraints. A constraint is something that blocks the player from completing the puzzle until they perform the correct solution. A basic example of a constraint is a locked door. The door prevents the player from progressing until they get the required key. Other examples of constraints are unreachable objects, limited choices of movement, and so on.

Another type of constrant is one built into your game mechanics. For example, if your player can push boxes, but can’t pull them, that is a constraint. With this constraint you could create puzzles where the player must push boxes around without moving the boxes to places where they can’t be pushed from (e.g. if the box is pushed all the way into a wall to the left, the player will not be able to push the box away from the wall because they can’t get to the left of the box due to the wall).

When you give the player some constraints they can overcome with the correct use of your puzzle mechanics, you have a puzzle.

Clear Communication

Make sure your puzzles are easy to interpret so the player doesn’t have to spend effort working out what they are supposed to achieve.

Distinguishing items in your puzzle or level, for example by colour, helps the player to read the puzzle and focus on finding a soluiton.

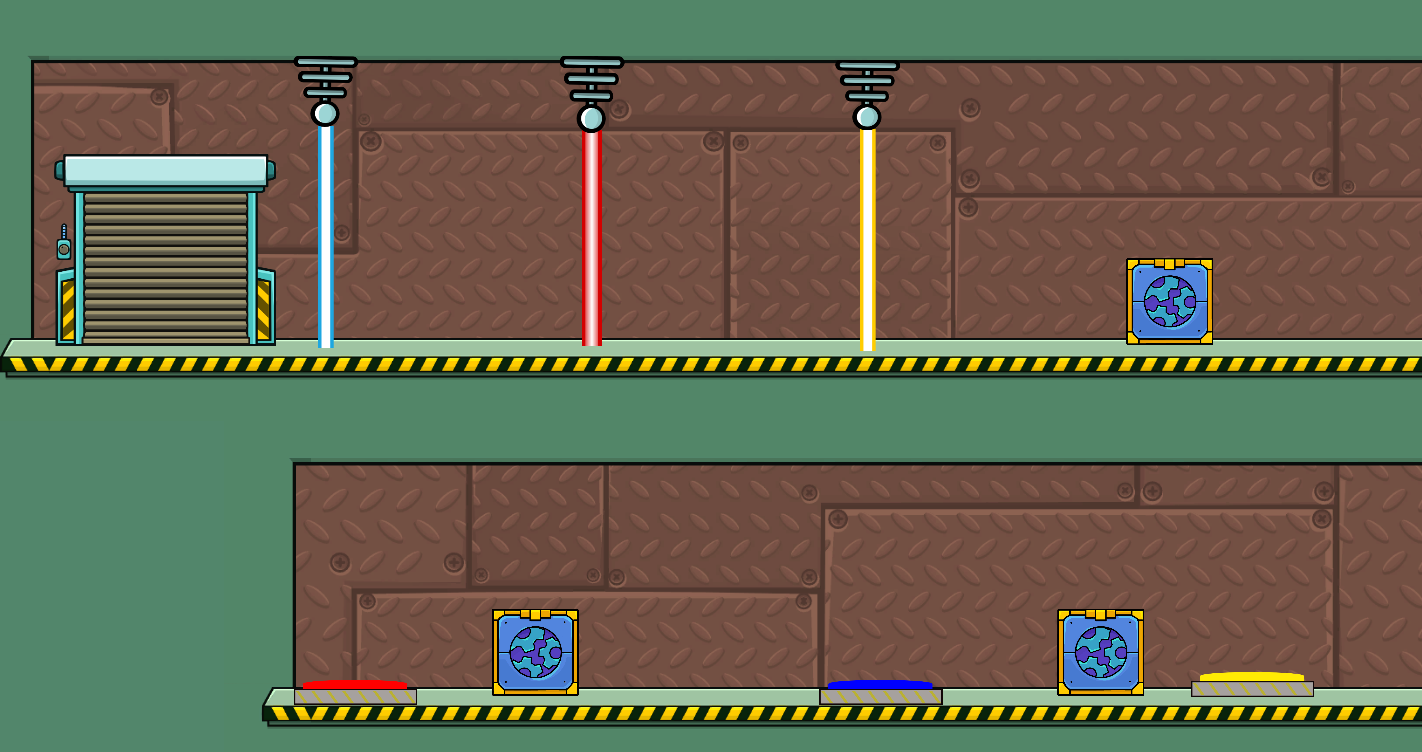

Take the example below from a game I’m currently working on. There are three laser beams which the player needs to disable in order to complete the level. There are three buttons that each disables one of the laser beams. As you can see, the buttons have colours that match the laser beams, so the player knows that to disable the red laser they need to push the red button, and so on.

This may at first seem like it’s giving away part of the solution, but that isn’t the case. If all the lasers and buttons and lasers were the same colour, would that make the puzzle better? Here is what this same puzzle would look like if different colours weren’t used:

The puzzle will be more difficult to solve, but only because the player needs to use some brute force to figure out which button disables which laser. But that extra time and effort would be spent doing something uninteresting, and adds nothing to the challenge besides a bit of extra busy work. The real challenge of the puzzle is to figure out how to use what’s available to disable the laser beams at the appropriate time to let the player reach the exit.

If the puzzle is interesting enough, you don’t need to obscure elements to introduce cheap difficulty and complexity. Help the player to understand the puzzle so they can focus all their energy on solving it.

This extends to other aspects of puzzles, such as making the objective clear. In the game above, the objective is to reach the exit door, and the exit is always visible to the player. Obstacles block the way to the exit, and various game objects and mechanics are there to be used in the correct ways and combinations to unblock the way to the exit.

The rules of your puzzles should generally stay the same throughout the game. In The Witness, every puzzle is a maze. There are a variety of twists on that basic context, but in every puzzle the player knows they need to draw a line from the start of the maze to the exit.

Give the Solution

This may seem counter-intuitive, but it’s quite important. Some types of puzzles. In a point-and-click adventure game you might have a puzzle that is a combination lock with 4 digits. You obviously wouldn’t expect the player to just guess the solution. You need to give the player a reasonable chance of finding the right solution. The solution can’t be something so obscure that an average player will never find it. Make sure the solution is reasonably close to the puzzle – you shouldn’t place a solution early in the game for a puzzle that shows up at the end. But you should of course obscure the solution. There are countless ways to disguise a combination code – for example, a shopping list on the fridge for 3 loaves of bread, half a dozen eggs, 2 pounds of raisins, and a bottle of cola (3-6-2-1).

Working out what needs to be done is not a fun part of solving a puzzle. Don’t require the player to do that. Think of it like a sport. You wouldn’t throw a ball to a bunch of people who have never played soccer before and expect them to work out the rules. Tell them the rules, set the parameters, and let them focus on the fun part – playing the game.

Make it Easy to Play

A player needs to be able to immediately start working on solving a puzzle. Don’t make it difficult to try a solution or to just get stuck in. It’s not clever to obscure the puzzle’s gameplay, and it’s definitely not fun either. A satisfying puzzle lets the player immediately get started, then presents them with a challenge by the various ideas and mechanics used in the puzzle.

As an extreme example, if you have a puzzle platformer, tell the player the controls. Don’t expect the player to use trial-and-error to figure out how to do basic movement. If the player has a special ability, make sure they know about it. As another extreme and unrealistic example purely for demonstration, if your player needs to pick up objects and carry them to another place, make sure they know that is an option, or the player may get frustrated at the objects in their way. Some game makers think that hiding information from the player makes a game more challenging. In a way it does, but it’s not the kind of challenging that is fun or interesting.

When the player tries something that won’t work, your game and puzzle design needs to make it clear to the player. For example, if you have a gap that the player needs to jump over, the player should be able to jump it easily without having to time their jump perfectly. If there is a gap that is too wide for the player to jump, it needs to be wide enough so that the player immediately knows they can’t jump it, either by sight, or by trying it once and missing by enough distance that it is clear they can’t make the jump.

Making the Wrong Move the Right Move

If your puzzle has actions that will lead to failure, you can sometimes use these to create trickiness in your puzzles.

Take this example from the game Cosmic Express:

For those who haven’t played the game: In Cosmic Express you must draw a train track through the level such that when the train follows the track from the entry to the exit, it picks up each alien and drops them off into the appropriately coloured house. In this level your train can hold two aliens at any time.

By the time you get to this puzzle in Cosmic Express, you have learned that you can’t pick up two aliens at the same time because they refuse to both board into the same train car. So if you draw the train track through the middle of the two purple aliens at the top-left corner near the entrance, neither will get in the train. The player has learned to draw the tracks so that this situation is avoided. This puzzle uses this learned assumption to mislmisdirect the player.

If you don’t mind spoilers for this one puzzle, read ahead.

Below is the solution to this puzzle. The entrance is in the upper-left, and the exit is down the bottom. As the player has learned from previous puzzles, to pick up the first two purple aliens, they must draw the track to ensure they only pass one alien at a time. Then they find a situation where there is no way to pass through two orane aliens without going straight through the middle. There isn’t room to loop around and collect one orange alien at a time, and therefore, if moving in this direction the player can’t collect the orange aliens.

The player knows (assumes) that moving past the orange aliens without picking them up is bad, and will cause them to fail the level. So most players will probably go back to square one and try a different approach such as drawing the track downwards and reaching the orange aliens from the other side where they can loop around. But the player will soon find that they can’t do that without blocking themselves from collecting the purple aliens.

What a conundrum! Both directions the player can draw their track appear to result in an impossible situation.

Here is the final solution:

The solution to this puzzle is to place the track in the ‘wrong’ place by drawing it through the orange aliens (they will refuse to board), and then to loop around to pass the orange aliens a second time, this time only passing one at a time. There is space to place the track to pick one up at a time. The player has to overcome a blind spot caused by their assumption. They have to do something counter-intuitive, but (and this is important) completely fair and consistent with the rules of the game.

In a way, the player is tricking themselves into a false limitation. The game doesn’t teach the player that they can’t place a track that passes by two aliens simultaneously, it just teaches that passing two aliens at the same time prevents the aliens from boarding the train. The player makes the incorrect assumption that they should always avoid passing two aliens at once.

This puzzle is satisfying to solve because there is a revelation when the player realises that they made an incorrect assumption. They also have learned that not only did the solution require ignoring that assumption, but that they now have another tool in their puzzle-solving toolbelt for this game, as it is likely that a similar scenario will pop up in other puzzles.

Backtracking

Puzzles tend to have a linear structure, e.g. get the green key, open the green door. To make your puzzles more interesting, and also to add more complexity and difficulty, create moments where the player needs to solve them non-linearly.

You can do this by requiring the player to undo something they have previously done, or by making the solving of one element of the puzzle to cause a hindrance to another part. A simple example would be that opening a door causes another door to close.

This makes your puzzles more tricky and interesting. The example above from Cosmic Express uses a type of backtracking.

Puzzle Pieces

Sometimes you can create a puzzle by combining two or more puzzle fragments or pieces – small mini-puzzles that are generic enough to be repeateable throughout your game. You can also add these puzzle pieces into existing puzzles to increase the difficulty and/or complexity.

As an abstract example, imagine a puzzle with two actions that need to be done in the correct order. The puzzle may be interesting and worthwhile, but perhaps is too easy because it is not very complex – the player may be able to figure out the solution very quickly because there is a limited possibility space. By adding a third piece to the puzzle – which can be something simple like adding a ‘key and lock’ element – you can increase the complexity enough to give the player a bit more of a challenge.

This technique can be very helpful, but it must be used carefully. If you rely too much on adding complexity to increase difficulty you risk creating puzzles that are difficult because they are complex rather then difficult because they require the player to apply their understanding of the mechanics and/or see a new twist on the way the mechanics are used.